SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

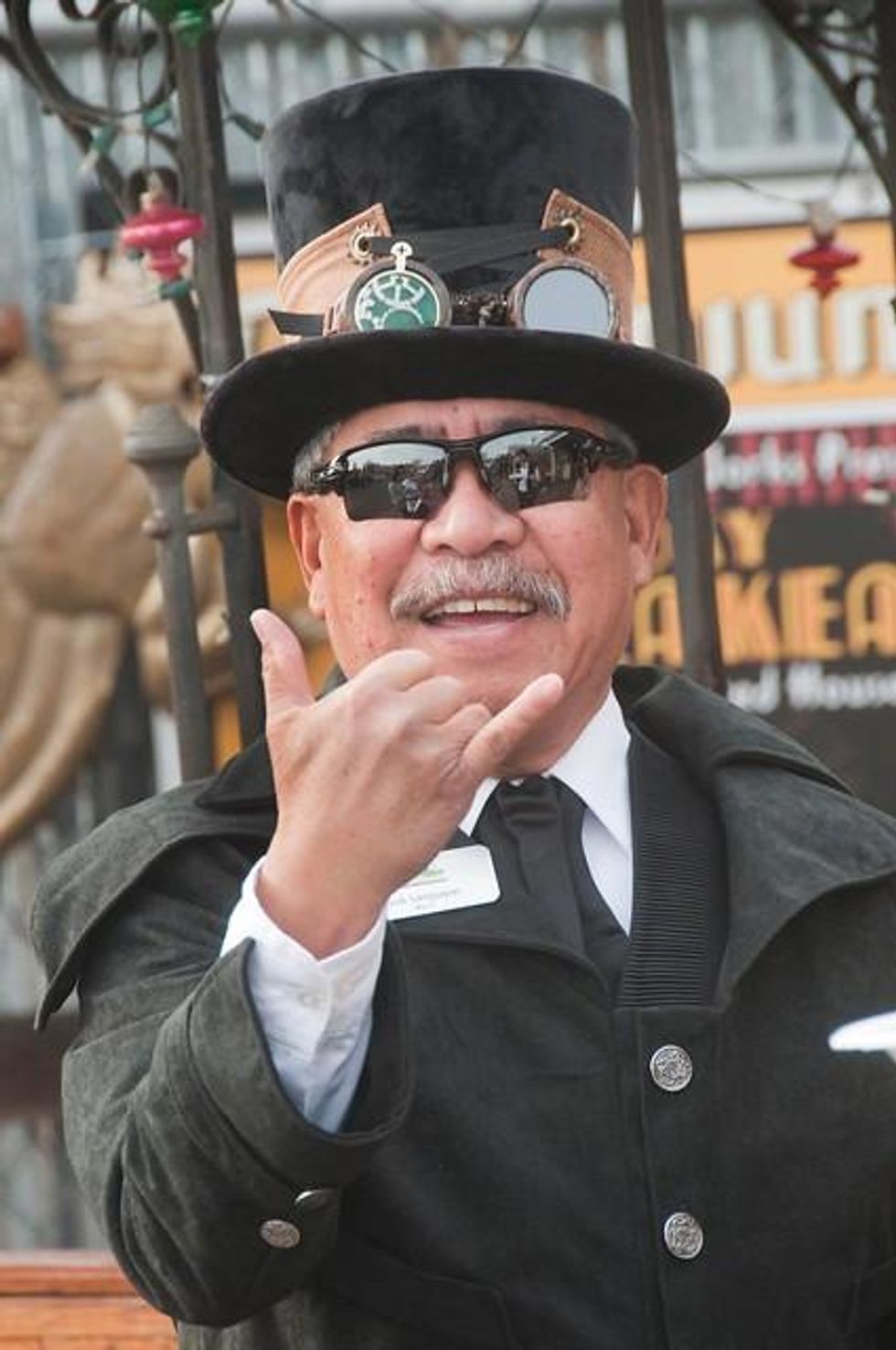

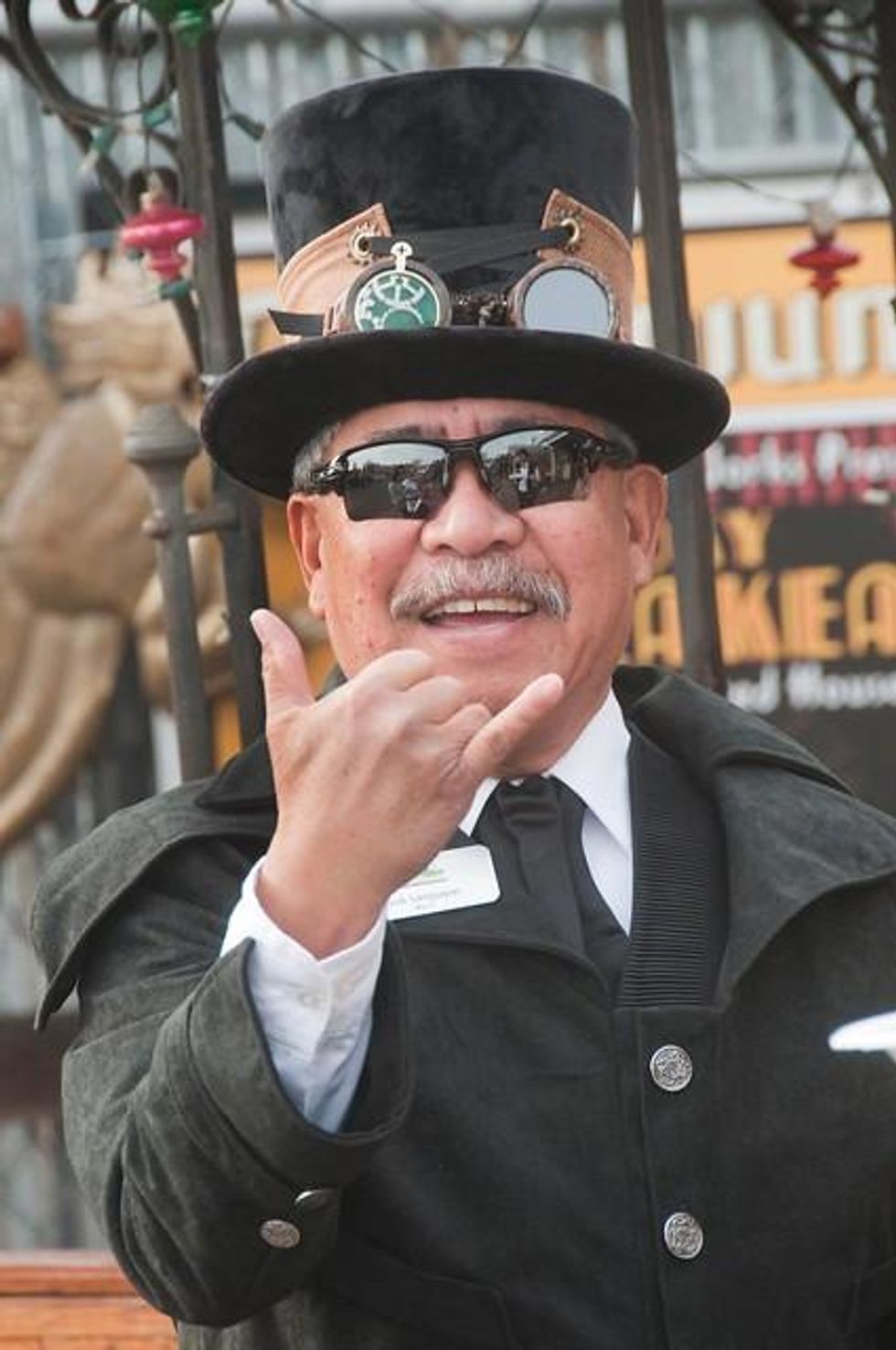

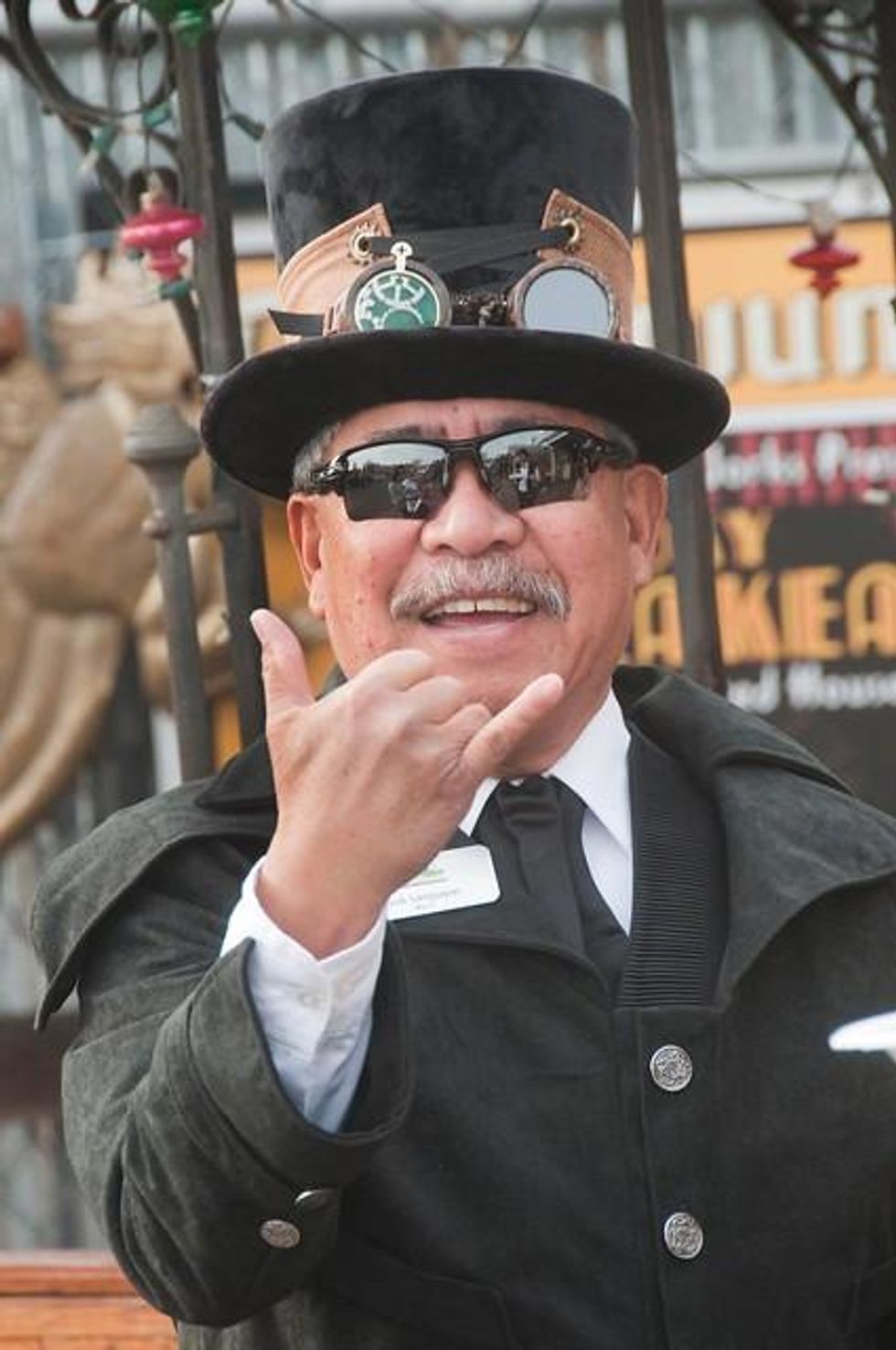

Vallejo has been hit hard by poverty, unemployment, and drug problems and was nearly devastated by the housing market crash of 2008, but its mayor believes the transformational power of beauty will help the city turn around. (photo by Patrick Nouhailler)

Bob Sampayan believes in the transformational power of beauty. Now in his sixties, Sampayan is the mayor of Vallejo, California, a primarily working-class city at the north end of San Francisco Bay that once built ships for the American Navy and for two brief periods in 1852 and 53, was the capital of the state. Vallejo has been called "America's most diverse city." A Brown University study found its population to be one-quarter white, one-quarter African-American, one-quarter Hispanic, and a final quarter Asian or Pacific Islander.

Sampayan himself is Filipino-American. He grew up in a military family in Salinas. They weren't so poor that he needed to work as a child, but his dad believed in the value of labor, and by the time he was 12, Sampayan was wielding a short-handled hoe in the lettuce fields near his home. He studied police science in college and served on Vallejo's police force for many years. He was elected mayor after he retired.

"Ever since I was a little kid I have admired nature's beauty," he told me, "everything from the coastal waters to the highest peaks. I carry that philosophy with me wherever I go... When I was young I'd go to Fremont Peak State Park near Salinas. I'd climb to the top for the beautiful view and the sense of peace I felt. It was my place. I'd spend nights there, just sitting looking at the stars."

With his crisp mustache and short-cropped, salt-and-pepper hair parted down the middle, Sampayan is a small man, but muscular, vigorous, and loquacious. An infectious smile frequently lights his tanned face. Mayor Bob, as he is often called, takes his job seriously, but himself less so. He is sometimes seen in parades wearing a Victorian top hat and aviator goggles, accessories of a style called "Steampunk." In fact, Sampayan bills himself as "America's first steampunk mayor."

But his job is no laughing matter. Sampayan took over the reins of a city that had been hit hard by poverty, unemployment, and drug problems and was nearly devastated by the housing market crash of 2008. Mayor Bob understands the need for economic development and welcomes business, but with a caveat. "I get business and industry," he says. "They keep our city alive, but some companies are gross polluters and I'm not going to stand for that. I want clean, safe and responsible energy, and I'm concerned about our waterways. A lot of chemicals are coming down the Sacramento River. I used to catch striped bass and flounder where the river comes into the Bay, but [the California] Fish and Game [Commission] is saying you can't eat them anymore."

Sampayan often takes his grandchildren for hikes in the local hills. They were a lush green after the winter rains and dotted with wildflowers when I visited him in April. "You get up there on the peaks and you overlook Vallejo," he says, gesturing with arms opened wide. But his excursions remind him that the lovely natural areas around his city bring ideas of a different kind of green to developers. "There's a possibility that the dollar will be worth more than the Earth itself, and that scares me," he laments. "Unfortunately, as the Bay Area has grown, we're encroaching on our last remaining open space and my prayer is that we don't. Vallejo hasn't had good stewardship of open space. We've focused on places to play baseball and fly kites. It's another thing to have parks that celebrate the beauty of the land."

Suburban sprawl has reached into Vallejo's hills, and its mayor lives at the edge of open space. Recently, some of his neighbors demanded that he call animal control to do something about the many coyotes, and even cougars, that residents had spotted not far from their homes. They were afraid for their children and pets. "People freaked out," he recalls with a grin. "'Well mayor, what are you going to do about this?'" His reply: nothing.

"We've taken their land and you're angry because there are indigenous creatures there," he told them. "You're out there with your little dog off the leash. We should say we're sorry we took their land. It belongs to everything from the red-legged frog to the mountain lion. If you don't want Fluffy to get eaten, you'd better put him on a leash."

Some people were angry, but when word got out about Sampayan's defense of wildlife, he was flooded with mail. "They were writing to tell me, 'Thanks for saying that!'" "We have to respect what nature we have left," he adds, "but most of all we have to celebrate it."

Given his views, it's perhaps no surprise that Mayor Sampayan supports And Beauty for All, a celebratory new national campaign to unite polarized Americans around environmental restoration, rural revitalization, and people-friendly urban design, including more parks, and greater preservation of open space and natural areas in and around cities.

In March, Vallejo, with a population of 120,000, became the largest city to officially endorse the campaign, proclaiming that "beautiful places to live, work and play should be a birthright of all Americans, no matter their origin or income," because "beautiful surroundings and graceful urban design call us to awe and stewardship, reduce polarization and anger, make us kinder and less aggressive, awaken generosity in our hearts, and move us toward justice."

The idea for the campaign came from a wager by Doug Tompkins, the co-founder of the giant clothing chains North Face and Esprit. A climber, kayaker, skier, and all-around adventurer, Tompkins once declared that: "If anything can save the world, I'd put my money on beauty." He did just that, using earnings from the sale of his companies to buy up millions of acres of wild land in South America. When he died in a kayaking accident in 2015, his widow donated most of the land to the governments of Argentina and Chile to create a national park three times as big as Yellowstone and Yosemite combined.

I've seen firsthand how a fight to preserve beauty can unite a community in conflict in Nevada City, California, where so-called "hippies" and "rednecks" joined forces to prevent a power dam from destroying the spectacular South Yuba River, leading to many ongoing efforts toward sustainability.

The And Beauty for All campaign is based on previous eras in our history when beautification efforts improved quality of life and saved land for future generations. Drawn to the call of beauty, the Olmsteds created magnificent city parks. The City Beautiful Movement brought grace into grim metropolitan areas. In 1912, poet Vachel Lindsay walked across much of America preaching "the Gospel of Beauty," and calling for a "new localism" that would revive the American countryside.

John Muir and David Brower fought for national parks and wilderness areas. "Everybody needs beauty as well as bread," wrote Muir, who lived only 12 miles from Vallejo in Martinez, California. "Bread and beauty grow better together," observed ecologist Aldo Leopold, adding that human actions were right when they enhanced "the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community," wrong when they didn't.

More recently, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall and President Lyndon Johnson's wife Lady Bird convinced LBJ to launch a comprehensive "beautification campaign" in the 1960s. In February 1965, Johnson delivered a "Special Message to Congress on Conservation and Restoration of Natural Beauty." He began:

For centuries Americans have drawn strength and inspiration from the beauty of our country. It would be a neglectful generation indeed, indifferent alike to the judgment of history and the command of principle, which failed to preserve and extend such a heritage for its descendants.

Johnson went on to talk of population growth "swallowing" natural beauty, urbanization crowding out nature, and new technologies "menacing the world" with the waste they created. The problems, he argued, required a "new conservation" based not only on protection, but on "restoration and innovation." Its concern was not only nature, but the human spirit. "Beauty," Johnson said, "must not be just a holiday treat, but a part of our daily life," and provide "equal access for rich and poor, Negro and white, city dweller and farmer."

The campaign included beautification of Washington DC and other cities, Clean Air and Water Acts, the Land and Water Conservation Fund (now in danger of elimination), reforestation and restoration programs, removal of billboards from federal highways and the addition of many new national parks and wilderness areas.

On October 2, 1968, Johnson signed "Conservation's Grand Slam," four "beauty bills" creating the Redwoods and North Cascades National Parks, and the National Wild and Scenic Rivers and Scenic Trails systems. This year, on the 50th anniversary of those Acts, some American cities will celebrate And Beauty for All Day. Vallejo will be one of them.

Steve Dunsky, a video producer with the US Forest Service on Mare Island in Vallejo, has helped catalyze much of the move to beautify the city. "With support from the State of California," Dunsky says, "Vallejo teens are planting trees in some of its poorer neighborhoods. Local nonprofits and government agencies are restoring wetlands and managing citizen science projects. We also hold an annual Visions of the Wild festival to connect our residents, and especially our children, more closely with parks and nature. This year's, running from September 20-23, will include a photography exhibit called On Beauty, honoring the work of Doug Tompkins."

Sampayan is passionate about bringing nature into the city and getting Vallejo's children outside, one of the goals of Visions of the Wild. "We need to do everything we can to connect kids with nature," he says. "These young people are going to be the stewards of our beauty and if we don't reach them, we'll lose it."

When I asked Mayor Sampayan if he thought focusing on beauty could reduce polarization when America is more divided than at any time since the Civil War, his immediate response was: "Let me tell you a story." As a boy his family took him to Yosemite on vacation. He fell in love with the place. After high school, he and his brother bought a car and often returned to Yosemite Valley on weekends. They would pump up the volume on their music in the campground. "We were being stupid," he admits now. Other campers clearly didn't like it, and one evening a man came over to talk with them.

"He didn't yell at us," Bob remembers. "If he had, we'd probably have yelled back and escalated the whole thing. He just calmly asked us why were there. We said we loved it because it was a beautiful place. He told us he did too, and for his family, a quiet escape from the city and the sounds of nature were part of the beauty. He asked us to respect that. We thought about it and had to admit he was right. We ended up becoming friends with his whole family. So, yes, I know what beauty can do."

But beauty, he's quick to point out, is about more than nature. Vallejo is actively involved in historic preservation of its lovely century-old Victorians. "The revitalization of our downtown includes an emphasis on public art, a Second Friday Art Walk, and a self-guided Art and Architecture Walk." In lower-income areas like Vallejo, beautification sometimes leads to gentrification and displacement of poor residents. Sampayan hopes to prevent that by concentrating efforts in less advantaged neighborhoods, on home ownership and upkeep requirements for landlords. It's a matter of environmental justice.

"We have paint grants, mending grants, "he explains. "We went through bankruptcy but helped people keep their homes through neighborhood loans. We have many absentee landlords who neglect their properties, so we established a specialized Multi-Agency Response Team to address blight and we filed suit against some property owners for causing it. We want more disadvantaged people to become homeowners because then they'll care more about keeping their homes beautiful. We also don't want homes torn down to create high-rise concrete jungles. And we want to move toward landscaping that is beautiful but not wasteful of resources."

It's an ambitious plan, designed for beauty and harmony with nature and wildlife. It will keep the mayor busy for the foreseeable future, but he still plans to find time to observe beauty outside of Vallejo too. "I climbed Half Dome three years ago," he says with pride. "It was on my bucket list. I just can't get enough of Yosemite." John Muir should be smiling.

This article was originally published July 18, 2018 in Earth Island Journal. A version of this article will appear in the magazine Wild Hope this coming fall.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Bob Sampayan believes in the transformational power of beauty. Now in his sixties, Sampayan is the mayor of Vallejo, California, a primarily working-class city at the north end of San Francisco Bay that once built ships for the American Navy and for two brief periods in 1852 and 53, was the capital of the state. Vallejo has been called "America's most diverse city." A Brown University study found its population to be one-quarter white, one-quarter African-American, one-quarter Hispanic, and a final quarter Asian or Pacific Islander.

Sampayan himself is Filipino-American. He grew up in a military family in Salinas. They weren't so poor that he needed to work as a child, but his dad believed in the value of labor, and by the time he was 12, Sampayan was wielding a short-handled hoe in the lettuce fields near his home. He studied police science in college and served on Vallejo's police force for many years. He was elected mayor after he retired.

"Ever since I was a little kid I have admired nature's beauty," he told me, "everything from the coastal waters to the highest peaks. I carry that philosophy with me wherever I go... When I was young I'd go to Fremont Peak State Park near Salinas. I'd climb to the top for the beautiful view and the sense of peace I felt. It was my place. I'd spend nights there, just sitting looking at the stars."

With his crisp mustache and short-cropped, salt-and-pepper hair parted down the middle, Sampayan is a small man, but muscular, vigorous, and loquacious. An infectious smile frequently lights his tanned face. Mayor Bob, as he is often called, takes his job seriously, but himself less so. He is sometimes seen in parades wearing a Victorian top hat and aviator goggles, accessories of a style called "Steampunk." In fact, Sampayan bills himself as "America's first steampunk mayor."

But his job is no laughing matter. Sampayan took over the reins of a city that had been hit hard by poverty, unemployment, and drug problems and was nearly devastated by the housing market crash of 2008. Mayor Bob understands the need for economic development and welcomes business, but with a caveat. "I get business and industry," he says. "They keep our city alive, but some companies are gross polluters and I'm not going to stand for that. I want clean, safe and responsible energy, and I'm concerned about our waterways. A lot of chemicals are coming down the Sacramento River. I used to catch striped bass and flounder where the river comes into the Bay, but [the California] Fish and Game [Commission] is saying you can't eat them anymore."

Sampayan often takes his grandchildren for hikes in the local hills. They were a lush green after the winter rains and dotted with wildflowers when I visited him in April. "You get up there on the peaks and you overlook Vallejo," he says, gesturing with arms opened wide. But his excursions remind him that the lovely natural areas around his city bring ideas of a different kind of green to developers. "There's a possibility that the dollar will be worth more than the Earth itself, and that scares me," he laments. "Unfortunately, as the Bay Area has grown, we're encroaching on our last remaining open space and my prayer is that we don't. Vallejo hasn't had good stewardship of open space. We've focused on places to play baseball and fly kites. It's another thing to have parks that celebrate the beauty of the land."

Suburban sprawl has reached into Vallejo's hills, and its mayor lives at the edge of open space. Recently, some of his neighbors demanded that he call animal control to do something about the many coyotes, and even cougars, that residents had spotted not far from their homes. They were afraid for their children and pets. "People freaked out," he recalls with a grin. "'Well mayor, what are you going to do about this?'" His reply: nothing.

"We've taken their land and you're angry because there are indigenous creatures there," he told them. "You're out there with your little dog off the leash. We should say we're sorry we took their land. It belongs to everything from the red-legged frog to the mountain lion. If you don't want Fluffy to get eaten, you'd better put him on a leash."

Some people were angry, but when word got out about Sampayan's defense of wildlife, he was flooded with mail. "They were writing to tell me, 'Thanks for saying that!'" "We have to respect what nature we have left," he adds, "but most of all we have to celebrate it."

Given his views, it's perhaps no surprise that Mayor Sampayan supports And Beauty for All, a celebratory new national campaign to unite polarized Americans around environmental restoration, rural revitalization, and people-friendly urban design, including more parks, and greater preservation of open space and natural areas in and around cities.

In March, Vallejo, with a population of 120,000, became the largest city to officially endorse the campaign, proclaiming that "beautiful places to live, work and play should be a birthright of all Americans, no matter their origin or income," because "beautiful surroundings and graceful urban design call us to awe and stewardship, reduce polarization and anger, make us kinder and less aggressive, awaken generosity in our hearts, and move us toward justice."

The idea for the campaign came from a wager by Doug Tompkins, the co-founder of the giant clothing chains North Face and Esprit. A climber, kayaker, skier, and all-around adventurer, Tompkins once declared that: "If anything can save the world, I'd put my money on beauty." He did just that, using earnings from the sale of his companies to buy up millions of acres of wild land in South America. When he died in a kayaking accident in 2015, his widow donated most of the land to the governments of Argentina and Chile to create a national park three times as big as Yellowstone and Yosemite combined.

I've seen firsthand how a fight to preserve beauty can unite a community in conflict in Nevada City, California, where so-called "hippies" and "rednecks" joined forces to prevent a power dam from destroying the spectacular South Yuba River, leading to many ongoing efforts toward sustainability.

The And Beauty for All campaign is based on previous eras in our history when beautification efforts improved quality of life and saved land for future generations. Drawn to the call of beauty, the Olmsteds created magnificent city parks. The City Beautiful Movement brought grace into grim metropolitan areas. In 1912, poet Vachel Lindsay walked across much of America preaching "the Gospel of Beauty," and calling for a "new localism" that would revive the American countryside.

John Muir and David Brower fought for national parks and wilderness areas. "Everybody needs beauty as well as bread," wrote Muir, who lived only 12 miles from Vallejo in Martinez, California. "Bread and beauty grow better together," observed ecologist Aldo Leopold, adding that human actions were right when they enhanced "the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community," wrong when they didn't.

More recently, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall and President Lyndon Johnson's wife Lady Bird convinced LBJ to launch a comprehensive "beautification campaign" in the 1960s. In February 1965, Johnson delivered a "Special Message to Congress on Conservation and Restoration of Natural Beauty." He began:

For centuries Americans have drawn strength and inspiration from the beauty of our country. It would be a neglectful generation indeed, indifferent alike to the judgment of history and the command of principle, which failed to preserve and extend such a heritage for its descendants.

Johnson went on to talk of population growth "swallowing" natural beauty, urbanization crowding out nature, and new technologies "menacing the world" with the waste they created. The problems, he argued, required a "new conservation" based not only on protection, but on "restoration and innovation." Its concern was not only nature, but the human spirit. "Beauty," Johnson said, "must not be just a holiday treat, but a part of our daily life," and provide "equal access for rich and poor, Negro and white, city dweller and farmer."

The campaign included beautification of Washington DC and other cities, Clean Air and Water Acts, the Land and Water Conservation Fund (now in danger of elimination), reforestation and restoration programs, removal of billboards from federal highways and the addition of many new national parks and wilderness areas.

On October 2, 1968, Johnson signed "Conservation's Grand Slam," four "beauty bills" creating the Redwoods and North Cascades National Parks, and the National Wild and Scenic Rivers and Scenic Trails systems. This year, on the 50th anniversary of those Acts, some American cities will celebrate And Beauty for All Day. Vallejo will be one of them.

Steve Dunsky, a video producer with the US Forest Service on Mare Island in Vallejo, has helped catalyze much of the move to beautify the city. "With support from the State of California," Dunsky says, "Vallejo teens are planting trees in some of its poorer neighborhoods. Local nonprofits and government agencies are restoring wetlands and managing citizen science projects. We also hold an annual Visions of the Wild festival to connect our residents, and especially our children, more closely with parks and nature. This year's, running from September 20-23, will include a photography exhibit called On Beauty, honoring the work of Doug Tompkins."

Sampayan is passionate about bringing nature into the city and getting Vallejo's children outside, one of the goals of Visions of the Wild. "We need to do everything we can to connect kids with nature," he says. "These young people are going to be the stewards of our beauty and if we don't reach them, we'll lose it."

When I asked Mayor Sampayan if he thought focusing on beauty could reduce polarization when America is more divided than at any time since the Civil War, his immediate response was: "Let me tell you a story." As a boy his family took him to Yosemite on vacation. He fell in love with the place. After high school, he and his brother bought a car and often returned to Yosemite Valley on weekends. They would pump up the volume on their music in the campground. "We were being stupid," he admits now. Other campers clearly didn't like it, and one evening a man came over to talk with them.

"He didn't yell at us," Bob remembers. "If he had, we'd probably have yelled back and escalated the whole thing. He just calmly asked us why were there. We said we loved it because it was a beautiful place. He told us he did too, and for his family, a quiet escape from the city and the sounds of nature were part of the beauty. He asked us to respect that. We thought about it and had to admit he was right. We ended up becoming friends with his whole family. So, yes, I know what beauty can do."

But beauty, he's quick to point out, is about more than nature. Vallejo is actively involved in historic preservation of its lovely century-old Victorians. "The revitalization of our downtown includes an emphasis on public art, a Second Friday Art Walk, and a self-guided Art and Architecture Walk." In lower-income areas like Vallejo, beautification sometimes leads to gentrification and displacement of poor residents. Sampayan hopes to prevent that by concentrating efforts in less advantaged neighborhoods, on home ownership and upkeep requirements for landlords. It's a matter of environmental justice.

"We have paint grants, mending grants, "he explains. "We went through bankruptcy but helped people keep their homes through neighborhood loans. We have many absentee landlords who neglect their properties, so we established a specialized Multi-Agency Response Team to address blight and we filed suit against some property owners for causing it. We want more disadvantaged people to become homeowners because then they'll care more about keeping their homes beautiful. We also don't want homes torn down to create high-rise concrete jungles. And we want to move toward landscaping that is beautiful but not wasteful of resources."

It's an ambitious plan, designed for beauty and harmony with nature and wildlife. It will keep the mayor busy for the foreseeable future, but he still plans to find time to observe beauty outside of Vallejo too. "I climbed Half Dome three years ago," he says with pride. "It was on my bucket list. I just can't get enough of Yosemite." John Muir should be smiling.

This article was originally published July 18, 2018 in Earth Island Journal. A version of this article will appear in the magazine Wild Hope this coming fall.

Bob Sampayan believes in the transformational power of beauty. Now in his sixties, Sampayan is the mayor of Vallejo, California, a primarily working-class city at the north end of San Francisco Bay that once built ships for the American Navy and for two brief periods in 1852 and 53, was the capital of the state. Vallejo has been called "America's most diverse city." A Brown University study found its population to be one-quarter white, one-quarter African-American, one-quarter Hispanic, and a final quarter Asian or Pacific Islander.

Sampayan himself is Filipino-American. He grew up in a military family in Salinas. They weren't so poor that he needed to work as a child, but his dad believed in the value of labor, and by the time he was 12, Sampayan was wielding a short-handled hoe in the lettuce fields near his home. He studied police science in college and served on Vallejo's police force for many years. He was elected mayor after he retired.

"Ever since I was a little kid I have admired nature's beauty," he told me, "everything from the coastal waters to the highest peaks. I carry that philosophy with me wherever I go... When I was young I'd go to Fremont Peak State Park near Salinas. I'd climb to the top for the beautiful view and the sense of peace I felt. It was my place. I'd spend nights there, just sitting looking at the stars."

With his crisp mustache and short-cropped, salt-and-pepper hair parted down the middle, Sampayan is a small man, but muscular, vigorous, and loquacious. An infectious smile frequently lights his tanned face. Mayor Bob, as he is often called, takes his job seriously, but himself less so. He is sometimes seen in parades wearing a Victorian top hat and aviator goggles, accessories of a style called "Steampunk." In fact, Sampayan bills himself as "America's first steampunk mayor."

But his job is no laughing matter. Sampayan took over the reins of a city that had been hit hard by poverty, unemployment, and drug problems and was nearly devastated by the housing market crash of 2008. Mayor Bob understands the need for economic development and welcomes business, but with a caveat. "I get business and industry," he says. "They keep our city alive, but some companies are gross polluters and I'm not going to stand for that. I want clean, safe and responsible energy, and I'm concerned about our waterways. A lot of chemicals are coming down the Sacramento River. I used to catch striped bass and flounder where the river comes into the Bay, but [the California] Fish and Game [Commission] is saying you can't eat them anymore."

Sampayan often takes his grandchildren for hikes in the local hills. They were a lush green after the winter rains and dotted with wildflowers when I visited him in April. "You get up there on the peaks and you overlook Vallejo," he says, gesturing with arms opened wide. But his excursions remind him that the lovely natural areas around his city bring ideas of a different kind of green to developers. "There's a possibility that the dollar will be worth more than the Earth itself, and that scares me," he laments. "Unfortunately, as the Bay Area has grown, we're encroaching on our last remaining open space and my prayer is that we don't. Vallejo hasn't had good stewardship of open space. We've focused on places to play baseball and fly kites. It's another thing to have parks that celebrate the beauty of the land."

Suburban sprawl has reached into Vallejo's hills, and its mayor lives at the edge of open space. Recently, some of his neighbors demanded that he call animal control to do something about the many coyotes, and even cougars, that residents had spotted not far from their homes. They were afraid for their children and pets. "People freaked out," he recalls with a grin. "'Well mayor, what are you going to do about this?'" His reply: nothing.

"We've taken their land and you're angry because there are indigenous creatures there," he told them. "You're out there with your little dog off the leash. We should say we're sorry we took their land. It belongs to everything from the red-legged frog to the mountain lion. If you don't want Fluffy to get eaten, you'd better put him on a leash."

Some people were angry, but when word got out about Sampayan's defense of wildlife, he was flooded with mail. "They were writing to tell me, 'Thanks for saying that!'" "We have to respect what nature we have left," he adds, "but most of all we have to celebrate it."

Given his views, it's perhaps no surprise that Mayor Sampayan supports And Beauty for All, a celebratory new national campaign to unite polarized Americans around environmental restoration, rural revitalization, and people-friendly urban design, including more parks, and greater preservation of open space and natural areas in and around cities.

In March, Vallejo, with a population of 120,000, became the largest city to officially endorse the campaign, proclaiming that "beautiful places to live, work and play should be a birthright of all Americans, no matter their origin or income," because "beautiful surroundings and graceful urban design call us to awe and stewardship, reduce polarization and anger, make us kinder and less aggressive, awaken generosity in our hearts, and move us toward justice."

The idea for the campaign came from a wager by Doug Tompkins, the co-founder of the giant clothing chains North Face and Esprit. A climber, kayaker, skier, and all-around adventurer, Tompkins once declared that: "If anything can save the world, I'd put my money on beauty." He did just that, using earnings from the sale of his companies to buy up millions of acres of wild land in South America. When he died in a kayaking accident in 2015, his widow donated most of the land to the governments of Argentina and Chile to create a national park three times as big as Yellowstone and Yosemite combined.

I've seen firsthand how a fight to preserve beauty can unite a community in conflict in Nevada City, California, where so-called "hippies" and "rednecks" joined forces to prevent a power dam from destroying the spectacular South Yuba River, leading to many ongoing efforts toward sustainability.

The And Beauty for All campaign is based on previous eras in our history when beautification efforts improved quality of life and saved land for future generations. Drawn to the call of beauty, the Olmsteds created magnificent city parks. The City Beautiful Movement brought grace into grim metropolitan areas. In 1912, poet Vachel Lindsay walked across much of America preaching "the Gospel of Beauty," and calling for a "new localism" that would revive the American countryside.

John Muir and David Brower fought for national parks and wilderness areas. "Everybody needs beauty as well as bread," wrote Muir, who lived only 12 miles from Vallejo in Martinez, California. "Bread and beauty grow better together," observed ecologist Aldo Leopold, adding that human actions were right when they enhanced "the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community," wrong when they didn't.

More recently, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall and President Lyndon Johnson's wife Lady Bird convinced LBJ to launch a comprehensive "beautification campaign" in the 1960s. In February 1965, Johnson delivered a "Special Message to Congress on Conservation and Restoration of Natural Beauty." He began:

For centuries Americans have drawn strength and inspiration from the beauty of our country. It would be a neglectful generation indeed, indifferent alike to the judgment of history and the command of principle, which failed to preserve and extend such a heritage for its descendants.

Johnson went on to talk of population growth "swallowing" natural beauty, urbanization crowding out nature, and new technologies "menacing the world" with the waste they created. The problems, he argued, required a "new conservation" based not only on protection, but on "restoration and innovation." Its concern was not only nature, but the human spirit. "Beauty," Johnson said, "must not be just a holiday treat, but a part of our daily life," and provide "equal access for rich and poor, Negro and white, city dweller and farmer."

The campaign included beautification of Washington DC and other cities, Clean Air and Water Acts, the Land and Water Conservation Fund (now in danger of elimination), reforestation and restoration programs, removal of billboards from federal highways and the addition of many new national parks and wilderness areas.

On October 2, 1968, Johnson signed "Conservation's Grand Slam," four "beauty bills" creating the Redwoods and North Cascades National Parks, and the National Wild and Scenic Rivers and Scenic Trails systems. This year, on the 50th anniversary of those Acts, some American cities will celebrate And Beauty for All Day. Vallejo will be one of them.

Steve Dunsky, a video producer with the US Forest Service on Mare Island in Vallejo, has helped catalyze much of the move to beautify the city. "With support from the State of California," Dunsky says, "Vallejo teens are planting trees in some of its poorer neighborhoods. Local nonprofits and government agencies are restoring wetlands and managing citizen science projects. We also hold an annual Visions of the Wild festival to connect our residents, and especially our children, more closely with parks and nature. This year's, running from September 20-23, will include a photography exhibit called On Beauty, honoring the work of Doug Tompkins."

Sampayan is passionate about bringing nature into the city and getting Vallejo's children outside, one of the goals of Visions of the Wild. "We need to do everything we can to connect kids with nature," he says. "These young people are going to be the stewards of our beauty and if we don't reach them, we'll lose it."

When I asked Mayor Sampayan if he thought focusing on beauty could reduce polarization when America is more divided than at any time since the Civil War, his immediate response was: "Let me tell you a story." As a boy his family took him to Yosemite on vacation. He fell in love with the place. After high school, he and his brother bought a car and often returned to Yosemite Valley on weekends. They would pump up the volume on their music in the campground. "We were being stupid," he admits now. Other campers clearly didn't like it, and one evening a man came over to talk with them.

"He didn't yell at us," Bob remembers. "If he had, we'd probably have yelled back and escalated the whole thing. He just calmly asked us why were there. We said we loved it because it was a beautiful place. He told us he did too, and for his family, a quiet escape from the city and the sounds of nature were part of the beauty. He asked us to respect that. We thought about it and had to admit he was right. We ended up becoming friends with his whole family. So, yes, I know what beauty can do."

But beauty, he's quick to point out, is about more than nature. Vallejo is actively involved in historic preservation of its lovely century-old Victorians. "The revitalization of our downtown includes an emphasis on public art, a Second Friday Art Walk, and a self-guided Art and Architecture Walk." In lower-income areas like Vallejo, beautification sometimes leads to gentrification and displacement of poor residents. Sampayan hopes to prevent that by concentrating efforts in less advantaged neighborhoods, on home ownership and upkeep requirements for landlords. It's a matter of environmental justice.

"We have paint grants, mending grants, "he explains. "We went through bankruptcy but helped people keep their homes through neighborhood loans. We have many absentee landlords who neglect their properties, so we established a specialized Multi-Agency Response Team to address blight and we filed suit against some property owners for causing it. We want more disadvantaged people to become homeowners because then they'll care more about keeping their homes beautiful. We also don't want homes torn down to create high-rise concrete jungles. And we want to move toward landscaping that is beautiful but not wasteful of resources."

It's an ambitious plan, designed for beauty and harmony with nature and wildlife. It will keep the mayor busy for the foreseeable future, but he still plans to find time to observe beauty outside of Vallejo too. "I climbed Half Dome three years ago," he says with pride. "It was on my bucket list. I just can't get enough of Yosemite." John Muir should be smiling.

This article was originally published July 18, 2018 in Earth Island Journal. A version of this article will appear in the magazine Wild Hope this coming fall.